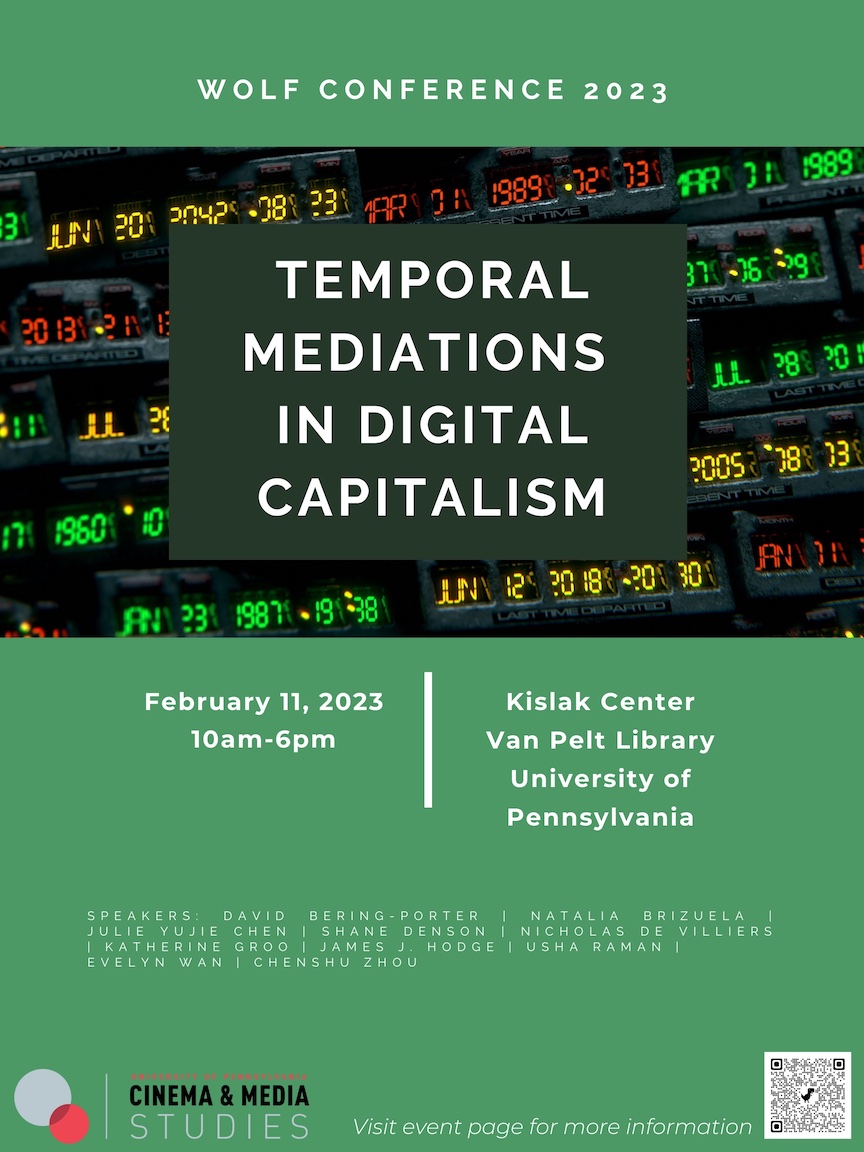

Event

Supported by a Dick Wolf Cinema and Media Studies Fund, this conference seeks to interrogate temporal practices and time-based media forms shaped in the current technological environment of digital capitalism. With the spread of digital networks, data, and algorithms, there has been a shared sense that clock time - a spatialized and rationalized modern conception of time symbolized by the clock - is insufficient for understanding the experiences and politics of time within the current form of global capitalism. Building on the interdisciplinary scholarship on time, media, and technology, this conference hopes to push the conversations about contemporary temporal mediations further in two directions:

I) To negotiate multiple, differential, and multiscalar temporalities: we hope to combine attention to technologically-determined temporalities with investigations into histories, institutions, and power dynamics that differentiate time for global populations divided along lines such as race, class, gender, and locality. We acknowledge that digital time, network time, or algorithmic time interact with deep time, historical time, postcolonial time, and personal time, resulting in the uneven organization of work and consumption across the Global North and South. Attending to such “messy” temporalities, the conference will consider both the structural and the lived, the infrastructural and the phenomenological of digital capitalism.

II) To connect studies of time-based digital media forms with the political economy of time, labor, and technology: the conference hopes to bring together scholars working from the interpretive traditions of film studies, art history, and cultural studies, and scholars applying social scientific methods to the study of media, technology, information, and communication. Bridging such a methodological divergence, the conference posits the investigations of creative forms and questions of technological and economic bases as mutually enriching. We encourage participants to delineate various neoliberal subjects, and examine the ways in which patterns of work, rest, consumption, and affects interact and unfold in lived temporalities.

__________________________________________________________________

PROGRAM OF THE CONFERENCE

10:00am | Breakfast

10:15-10:30am | Welcoming Remarks | Karen Redrobe and Chenshu Zhou

10:30-11:30am | Panel I: Archaeologies of Time | Moderator: Anat Dan

Evelyn Wan | Utrecht University | How We Lost Sense of Time: A Prehistory of Algorithmic Governance

Katherine Groo | Lafayette College | Time Change

11:30-11:45am | Coffee Break

11:45am-1:15pm | Panel II: (Un)timely Labor | Moderator: JS Wu

Julie Yujie Chen | University of Toronto | Temporal Labor for Practice that Makes Perfect in the Data Production for AI

Usha Raman | University of Hyderabad | For the Bangle Makers of Hyderabad, Time Folds Tightly in on Itself

Nicholas de Villiers | University of North Florida | Tsai Ming-liang’s Days: Sex Work as Care Work, Bounded Authenticity, and Slow Cinema

1:15-2:15pm | Lunch

2:15-3:45pm | Panel III: Time Forms | Moderator: Humberto Morales Cruz

Natalia Brizuela | UC Berkeley | The Future is Ancestral: Temporality and "Indigenous" Cinema

James J. Hodge | Northwestern University | Time Without Measure: The Animated GIF, the Supercut, and Always-On Computing

Chenshu Zhou | University of Pennsylvania | My CP is Real: Digital Temporality and the Cultural Politics of Fan "Munching"

3:45-4:00 | Coffee Break

4:00-5:00pm | Panel IV: Bodies of Capitalism | Moderator: Ethan Plaue

David Bering-Porter | The New School | Capitalist Surrealism: Undead Time and the Digital Zombie

Shane Denson | Stanford University | On the Temporal Technics of Metabolic Capitalism

5:00-6:00pm | Concluding Reflections | All Speakers

__________________________________________________________________

PRESENTERS, TITLES, AND ABSTRACTS IN ORDER OF THEIR APPERANCE AT THE PANELS

Evelyn Wan is Assistant Professor in Media, Arts, and Society at the Department of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University. Her work on the temporalities and politics of digital culture and algorithmic governance is interdisciplinary in nature, and straddles media and performance studies, gender and postcolonial theory, and legal and policy research. Her writings have appeared in International Journal of Communication, GPS: Global Performance Studies, Theatre Journal, and International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, amongst others.

How We Lost Sense of Time: A Prehistory of Algorithmic Governance

The prehistory to today's algorithmic governance is a story about how we lost sense of time in our bodies. I argue that mechanical time discipline is an imposition that make us forget the natural rhythms of our bodies, and is an earlier form of algorithmic governance that proceeded according to the rhythm of clocks. In our current digital era, algorithmic governance can be seen as an intensification of such time discipline, control, and management--a time-based governance that can be observed from gig economy labour to durational data extraction through (self-)tracking devices. In the presentation, I will highlight the corporeal and gender-based violence that underlie the history of clocks and time discipline through the mass murder of women through witch-hunting in the early modern period. Using Silvia Federici's work, I discuss how the biopolitics of time might have begun with the killing of wise women and eradication of magical and pagan practices which were against the order of the clock and the rhythm of capitalist production. The body perfect for capitalist labour extraction is a docile body that becomes part of its machinery. Temporality plays an important role in moulding and shaping the docile bodies, and the rhythms of machinic production require workers on an assembly line to literally recompose their bodies in time to form an efficient machine, much like how Amazon pickers, delivery personnel, and on-demand drivers have to work according to the rhythm of the apps. By revisiting this history, I aim to propose forms of resistance against the grip of time discipline and algorithmic governance over our bodies today. How might we regain our bodily senses of time through cultivating technologies of the self (Foucault) against technologies of power?

______________________________________________________

Katherine Groo is an assistant professor in Film and Media Studies at Lafayette College. Her essays have appeared in The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, Framework, Discourse, and Frames, as well as numerous edited collections. She is the author of Bad Film Histories: Ethnography and the Early Archive (University of Minnesota Press, 2019) and co-editor of New Silent Cinema (Routledge/AFI, 2015). She is also the recipient of the Alexander von Humboldt Experienced Research Fellowship. Her current book project examines the referentiality and artifactuality of contemporary visual media.

Time Change

In her foundational study of cinematic time—its technological emergence and interaction with turn-of-the-twentieth-century temporal concerns—Mary Ann Doane argues that the simultaneous promise and threat of cinema in its earliest incarnation was precisely its capacity to represent real time in all of its contingent, overwhelming detail. Cinema’s forward movements and relentless accumulation of any-instant-whatever, she writes, “gives witness to the erosion of organization and the free field of chance,” (23). As Doane outlines, the representational dilemmas of early cinema, that is, the problem of a boundless and potentially meaningless archive of time, eventually gets resolved through editing and the consolidation of narrative codes. In the end, time is brought under control. Meaning gets made through the exclusion of “real time” and the construction of “time as an effect,” (67). In Doane’s view, the one cinematic system functions something like magic; the other arrives as an expression of science, probability, and the ordering logic of statistics. In this paper, I am interested in considering what, if anything, this understanding of cinematic time—split between magic and science, the contingencies of real duration and the structures of statistics—might have to teach us about the temporal expressions of machine learning and contemporary computational image production (including user-oriented networks like Dall-E and Midjourney, among others). In my view, these image machines strangely invert the structures of cinematic temporality. They proliferate as so many magic little boxes of any-image-whatever, boundlessly generating contingent encounters with the present, with an instant that could always be otherwise. Put another way, these networks seem to embrace the threat of meaningless accumulation and archival non-sense. And yet, of course, they are intrinsically, fundamentally statistical tools whose very capacity to produce an image-instant depends upon the taxonomic systems of photo-film archives, statistical models for minimizing data loss, and an iterative algorithmic process. Indeed, recursion is the very condition of computability and fundamental to any understanding of machine learning. In other words, the contingency of these images is created “as an effect.” These images have a history, absented from the scene(s) of our encounter.

______________________________________________________

Julie Yujie Chen is Assistant Professor in the Institute of Communication, Culture, Information, and Technology (Mississauga) and holds a graduate appointment at the Faculty of Information (St. George) at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on the transformation of work and worker's life in relation to digital technology, capitalism, and globalization. She is the co-author of Media and Management (Minnesota, 2021) and Super-sticky WeChat and Chinese Society (Emerald, 2018). Her current project examines the labor regime for the data production in the context of data/digital capitalism in China.

Temporal Labor for Practice that Makes Perfect in the Data Production for AI

Just-in-time production has become a market principle in the transnational global supply for manufacturing and on-demand service mediated by digital platforms. This paper explores how just-in-time principles informed the transition from analogue to digital capitalism via a case of data annotation for machine learning (ML)/AI models in China and its ramifications. Platform-based data annotation workers are summoned and disbanded in a project-specific manner. The data annotation sector in China, however, also involves layers of intermediaries, which includes crowdwork platforms, leading annotation tech companies, small- and medium-sized annotation contractors with dozens of workers, and individual workers. The paper shows the inconsistences and paradoxes in the temporal configurations of data production for AI. It is argued that the layers of intermediaries facilitate the assembly of human as service for AI in an efficient manner but simultaneously undermines the delivery of just-in-time data production. Specifically, on one hand, the development timeframes of ML/AI models are informed by agile software development which emphasizes timely and quality communications in the feedback loop. On the other hand, the communication distance and unbalanced power between the tech company client and the frontline data annotation workers cause moments of disruption and inconsistence in the data production process, and all the more precarious thanks to layers of intermediaries. Moreover, the development of ML/AI models are subject to the anticipatory, strategic, and operational needs of the tech companies. The experimental character of some models is prone to produce uncertainty and confusion for workers when it comes to learn and apply the guidelines to the annotation work. Consequently, the temporal configuration of data production for AI contributes to unpredictable work paces and degrees of communicative labor required of data annotation workers, which makes learning and practice an integral part of the labor process.

______________________________________________________

Usha Raman is Professor and Chair, Department of Communication, University of Hyderabad, India. Her teaching and research interests span the areas of digital cultures, feminist media studies, journalism pedagogy, and critical science & technology studies. She is co-founder of FemLab, an academic-activist collective. Usha is currently serving as Vice-President of IAMCR (2020-24).

For the Bangle Makers of Hyderabad, Time Folds Tightly in on Itself

Women engaged in largely home-based artisanal crafts across the world form part of the informal work force that has in recent times become the focus of academic and policy attention in relation to the growing concern around the future of work, with issues such as precarity, working conditions, and social support dominating the conversation. Less understood and relatively less studied is working time and its contribution to time poverty—an idea that has gained traction in recent years. Home-based artisanal workers must deal with the blurred boundaries of work place and time as they engage in their craft, with domestic and carework leaking into parts of the day that may be set aside for paid work. Time therefore is a resource beyond the worker’s control, and there is never enough of it to monetise. In this paper, I draw insights from a research project that sought to understand how informal women workers negotiate with the structures and demands of work, and bring into conversation three themes that emerged from the field. The first is the commodified representation of heritage craft that decenters the artisan, positioning her in a historical capsule that renders her outside the reach of the discourse of labour rights. The second is the notion of time poverty, resulting in this case from the precarious and tedious conditions of artisanal work. The third has to do with the value of gendered work-time, arising from the collapsed contexts of the domestic and occupational.

______________________________________________________

Nicholas de Villiers is professor of English and film at the University of North Florida. He was a visiting scholar at National Central University in Taiwan at the Center for the Study of Sexualities (2017). He is the author of Opacity and the Closet: Queer Tactics in Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol (2012), Sexography: Sex Work in Documentary (2017), and Cruisy, Sleepy, Melancholy: Sexual Disorientation in the Films of Tsai Ming-liang (2022), all from the University of Minnesota Press.

Tsai Ming-liang’s Days: Sex Work as Care Work, Bounded Authenticity, and Slow Cinema

Many of the most significant publications on Taiwan-based filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang focus on questions of time—temporality and duration, but also nostalgia and melancholy—or what Song Hwee Lim has named “a cinema of slowness.” In my book Cruisy, Sleepy, Melancholy: Sexual Disorientation in the Films of Tsai Ming-liang, I contend that we also need a queer theory of space and spatial practices to understand Tsai’s cinematic exploration of feeling melancholy, cruisy, and sleepy—affects with temporal and spatial implications. This presentation builds on those arguments to address Tsai Ming-liang’s queer Teddy award-winning “post-retirement” digital film Days (Rizi, 2020), set in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Thailand, featuring Tsai’s male muse Lee Kang-sheng’s intimate encounter with Anong Houngheuangsy as a Laotian migrant male sex worker masseur in Bangkok. Their massage session with a “happy ending” is filmed in a hotel room in Bangkok, followed by a shared meal in a nearby restaurant. Days portrays queer sex work as a form of care work, since the film returns to treatments for Lee’s actual neck pain first incorporated into the plot of Tsai’s The River (Heliu, 1997). Tsai’s latest film thus raises issues of diasporic and queer temporality and labor, what Elizabeth Bernstein calls “bounded authenticity” in Temporarily Yours, and what Chris Berry has called “stranger intimacy” within Tsai’s films and queer culture. In a brief statement while accepting the Teddy award at the Berlinale for Days, Tsai dedicated the film to “my country” Taiwan and celebrated the marriage equality decision (the translator noted that Taiwan was the “first country in Asia” to pass “gay marriage”). Yet the film Days itself features a more liminal, queer, cross-class, inter-Asian, intergenerational, and commercial sexual relationship between Lee and Anong. I therefore consider questions of queer time and place—plus timing and space—in Tsai’s relation to his actors, queer cinema, and migrant sex work.

______________________________________________________

Natalia Brizuela writes and teaches about visual culture, art, film, media, literature and critical theory from Latin America, with a particular focus on experimental practices that bridge aesthetics and politics. She is the author of, among others, Fotografia e Imperio (2012), Depois da fotografia (2014), The Matter of Photography in the Americas (2018) and La cámara como método (2021) and has curated numerous exhibitions and film programs. She is currently co-preparing the online experimental exhibition Bits of the Planet with Rachel Price and Ian Alan Paul and finishing a book on the refusal of Time. She is Class of 1930 Chair of Letters & Sciences, the Director of the Center for Latin American Studies at UC Berkeley, and a Professor of Film & Media and Spanish & Portuguese.

The Future is Ancestral: Temporality and "Indigenous" Cinema

In my talk I will seek to complicate the notion of “aftermath” which is usually inscribed in a modern Western linear conception of time as a projection, and points, like an arrow, to a future that is to come afterwards. In coexistence to this modern Western notion of time as progress, other notions of temporality exist that can allow us to envision aftermaths that are ancestral, that are already here, that have been here all along and continue to be activated through constant cultivation and practice of memory and dream. Some of these ancestral futures structure the temporalities of indigenous people from across Abya Yala, including, among others, Mapuche and Krenak worlds. Such temporalities complicate the modern Western notion of futurity, not only by placing what has already happened before and ahead of what is yet to come, but also by insisting on a vital form of presence. The present does not quite vanish, but is in everything, always. This talk will explore these questions in conversation with different Indigenous conceptions of the image.

______________________________________________________

James J. Hodge is Associate Professor in the Department of English and the Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities at Northwestern University where he is also Director of Graduate Studies for the PhD program in Rhetoric, Media, and Publics. He is the author of many essays on digital aesthetics, and the author of Sensations of History: Animation and New Media Art (Minnesota, 2019). His current book project is entitled Ordinary Media: An Aesthetics of Always-On Computing.

Time Without Measure: The Animated GIF, the Supercut, and Always-On Computing

It is perhaps a twenty-first century truism that one does not experience time online so much as one loses it. From one point of view, we may observe the experiential withdrawal of digital technics from human perception and cognition and conclude that this historical condition has truly scrambled any sense of time anchored in Aristotle's famous idea of time as the measure of movement of a before and after. After all, it would seem that we have long since outsourced the work of temporal measurement to machines operating largely beyond our purview. From another perspective we may observe the curious proliferation of networked genres with the mid-2000s rise of always-on computing, or the milieu of smartphones, social media, and ubiquitous wireless networks. These include memes, selfies, tweets, likes, podcasts, ASMR, casual games, vaporwave, and much else. The sheer proliferation of new networked genres suggests the rise of various vernacular strategies of attuning oneself to the vicissitudes of the historical present, including new and difficult-to-articulate experiences of time. Among these genres the animated GIF and the supercut represent two promising sites for thinking through the changing nature of temporal experience today. Most intriguingly, these two genres formally solicit experiences of self-affection. In doing so they call upon an alternative conception of time in Western philosophy rooted not in measurement but in self-affection, a term used by Heidegger in his reading of Kant and with resonances in the work of Derrida, Merleau-Ponty, and others. For this project I suggest emphasizing and expanding the tradition of temporal self-affection as the ground of subjective experience as crucial for grasping after the technological condition of time today. To concretize and specify this idea I will pursue my discussion through the analysis of selected GIFs and supercuts.

______________________________________________________

Chenshu Zhou is Assistant Professor in the History of Art Department and the Cinema and Media Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of Cinema Off Screen: Moviegoing in Socialist China (University of California Press, 2021), winner of the Best First Book Award from the Society of Cinema and Media Studies. Her research centers on media experiences in modern and contemporary China. Her writings and translations have appeared in journals such as positions: asia critique, Journal of Chinese Cinemas, and Chinese Literature Today.

My CP is Real: Digital Temporality and the Cultural Politics of Fan "Munching"

Since the mid-2010s, the Chinese entertainment industry has thrived on a mode of fan engagement that centers on “coupling” (or CP in Chinese fandoms): the intimate, romantic, or erotic pairing of fictional characters or real-life celebrities, be they invented or actual. Scholarly interests in East Asian fandoms have been driven by questions of gender and sexuality, thus giving more attention to Boy’s Love, which involves coupling, while ignoring coupling as a general mode of fan consumption that cuts across lines of sexual orientation. This paper instead shifts focus onto another important dimension, that of temporality, to argue for the cultural and political significance of fan activities around coupling in the broader context of state-sponsored neoliberalism. I will describe the mode in which fans consume their favorite CPs as “munching” – a notion derived from the Chinese word ke (嗑). A gastronomical metaphor, ke originally refers to the teeth’s chopping motion when trying to crack open sunflower seeds (as in ke guazi), or the action of consuming substances (as in keyao). The connotations of both are acknowledged in the term “ke CP,” which evokes both fans’ savoring of minute details and a sense of involuntary addiction. Munching thus refers to transformative manipulations of digital imagery that privilege brief durations. Chinese fans employ a variety of munching techniques such as spotlighting, slow watching, reverse eyeline match, captioning, and montage to identify, inhabit, interpret, and prolong affective moments that contain what they see as evidence of love. The result of munching, I argue, is not the fabrication of fans’ wishful thinking, but the visualization of the virtual, which I identify with unactualized potentialities following other thinkers of the virtual, most notably Brian Massumi. Embedded in the interstices of digital time, the virtual, made visible only through digital means, offers a location (or duration) of escape for the strained neoliberal subject whose pursuits of future-oriented goals such as individual success and heternormative love are constantly demanded by neoliberal governance. To illustrate how munching queers normative temporalities, I will examine a recent reality talent show known as Chuang 2021. Fan munching disrupts the linearity of competition and the cruel optimism of meritocracy through a virtual realm of love that foregrounds the trafficking of bodily intensities in an ongoing present.

______________________________________________________

David Bering-Porter is Assistant Professor of Culture and Media at The New School in New York City. David has lectured, taught, and published on zombie movies and other forms of Black horror at the intersections of film, digital media, and technology. His current book project is a study of undead labor and the ways that race, labor, and value come together in the mediated body of the zombie as well as other examples of biological excess and his academic writing has appeared in journals such as Culture Machine, Critical Inquiry, Flow, MIRAJ, Post 45, and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Capitalist Surrealism: Undead Time and the Digital Zombie

At “The Dalí” – the Salvador Dalí museum in St. Petersburg, Florida – the Dalí Lives (via Artificial Intelligence) exhibition makes the unusual claim that you can really meet the artist. This meeting does not take place through close engagement with Dalí’s artworks, on exhibit at the museum, or through and traditional method of engaging with history of biography but, rather, through a large screen upon which a life-sized digital re-animation of Dalí will greet and interact with audience-members – speaking about his own life and work and responding to questions in Dalí’s own voice. Of course, Dalí died in 1989. So, just what is it that greets museumgoers in the Dalí museum? This “digital Dalí '' is created through the techniques and technologies of machine learning to precisely replicate the facial expressions, body movements, speech patterns, and basic mannerisms of Dalí himself. The algorithms learn to bring Dalí back from the dead, reanimating him piece by piece based on footage from when he was alive. Following a reading of the digital Dalí, this talk explores the effects and implications of the digital afterlife and looking beyond the Dalí Lives exhibition to other case studies such as the Replika app, a chatbot and “artificial friend” whose history also involves memorializing and bringing back the dead. Using the conceptual framework of undead time – the loops, repetitions, and temporal arrests that maintain and enforce the perpetual present of late capitalism – this talk asks how artificial intelligence and machine learning make it possible to put the dead to work in the digital milieu and thus paving the way for a new kind of zombie in the digital age.

______________________________________________________

Shane Denson is Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies in the Department of Art & Art History and Director of the PhD Program in Modern Thought & Literature at Stanford University. His research and teaching interests span a variety of media and historical periods, including phenomenological and media-philosophical approaches to film, digital media, comics, games, and serialized popular forms. He is the author of Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface (Transcript-Verlag/Columbia University Press, 2014), Discorrelated Images (Duke University Press, 2020), and co-editor of several anthologies.

On the Temporal Technics of Metabolic Capitalism

In this presentation, I hope to uncover the temporal dynamics of an emerging system of metabolic capitalism. This system takes aim at embodied and environmental exchanges, including organic processes such as heart rate, brainwave activity, and eye movement, targeting the body as both a resource to be mined and an object to be shaped. Wearables such as the Apple Watch, smart exercise machines like the Peloton or Mirror workout systems, and consumer-grade EEG devices marketed to help improve attention or to assist with mindfulness or meditation—all of these institute a system of “training” that aims to discipline the user’s bodymind and make it more productive. Unlike earlier disciplinary regimes, however, this newer one situates screens and other interfaces as the site of interactive real-time feedback between metabolic processes and subjective and social efforts to transform them. Accordingly, these apparatuses operationalize a temporality that undercuts the threshold of subjective perception, intervening directly in the prepersonal time of embodiment itself, thus enlisting users in an experiment with metabolic and phenomenological time that has far-reaching consequences for our embodied and social existences. (It goes without saying that corporations will extract value from the experiment regardless of its success or failure, however such outcomes might be defined.) From a media-theoretical perspective, the new interventions mark a significant update from the past-oriented or memorial functions of recording technologies like the cinema as well as the “ontology of liveness” or presence attaching to television; in their place, post-cinematic technologies such as those discussed here are future-oriented or protentional, and they therefore participate in a potential pre-formatting of subjectivity and embodiment. In political economic terms, these technologies therefore also mark an important update in the organization of social materiality itself; that is, they shift from what Sartre in his late, Marxist work identified as the “practico-inert” (in light of the way that commodities and other forms of “worked matter” store past human praxis while condensing it into inert objective form), to a futural technics of what I call the “practico-alert”—where proactively surveillant technologies intervene more directly in subjectivation processes and put us, like the new machines, in a constant state of alert. Finally, whereas Sartre’s practico-inert organized social structures around itself (Sartre’s class-oriented formation of the “seriality,” for example, which Iris Marion Young takes as the basis for thinking gender as a socially enforced typification process), these new futural technologies must be interrogated also in terms of their social agencies as important vectors of typification (racialization, gendering, and dis/abling, among others) and futural or preemptive interpellation.

______________________________________________________

The conference, free and open to the public, has been made possible thanks to the Dick Wolf Cinema & Media Studies Fund. It has been organized by Chenshu Zhou, Assistant Professor in the History of Art Department and the Cinema and Media Studies Program at Penn, with the assistance of Nicola M. Gentili, Associate Director of Cinema & Media Studies at Penn.

______________________________________________________